Moz Developer Blog

Moz engineers writing about the work we do and the tech we care about.

Introducing RogerOS Part 1

Posted by Arunabha Ghosh on December 7, 2015

Preamble

This is the first in a two-part blog post outlining our work at Moz on RogerOS, our next generation infrastructure platform. This post gives background for and provides an overview of the system. The second part provides the juicy technical details. This blog post comes to you courtesy of Arunabha Ghosh and Ankan Mukherjee. We hope you enjoy reading about it as much as we’ve enjoyed working on it.Introduction

A year ago, we set out to create a new platform for Moz Engineering. The premise was simple - build a next gen platform that would be the foundation for Moz’s engineering efforts and enable a quantum leap in developer productivity and resource efficiency. While the premise was simple, executing on the vision was a whole different ball game. This blog post details our efforts on building out the vision.Background

The past decade has seen a dramatic rate of change in the tech landscape. The inexorable wave of innovation in software, and the rapidly increasing set of industries innovating using software as the primary leverage, has meant software systems have evolved extremely rapidly with no signs of slowdown in the rate of change. Computing infrastructure has seen a similarly dramatic, if more gradual, rate of change. We have gone from in-house, proprietary, coupled, monolithic platforms to open source, distributed, loosely coupled platforms. The rate of change in this world has been impressive as well. However, infrastructure systems usually have much longer life spans than products, and as such, fitting ever newer software systems onto existing infrastructure has been a key challenge for organizations. At Moz we have faced the same problems. Continual innovation in our products is at the heart of what we do at Moz, and our customers deserve nothing less. However, as mentioned in the post last year, we were getting to the limits of our current systems. The most visible effect was on our development velocity. Iteration cycles were getting longer, and engineers were spending more and more of their time babysitting systems. There were other less (externally) visible problems as well. It was relatively difficult to get prototyping resources and be able to try out new things. Experimentation is the lifeblood of innovation, and we wanted to make it as easy as possible for our engineers and product managers to try out new ideas. Lack of easy access to resources also meant that teams would ‘hold on’ to resources, even if they were not being used fully, in anticipation of future needs. Things were not much easier for our tech ops team. They had to support a staggering set of possible combinations of language, frameworks, databases, etc. From a planning perspective, incoming resource requests were a nightmare as the requests they would get from dev teams were one-offs and ‘odd shaped’ in the sense each request was custom in terms of resource dimension. For example, one team might want lots of RAM and cores, but care little about disks, while another would need relatively low CPU and RAM, but lots of fast disks. This didn’t fit well with the procurement cycle for hardware. The reality is that hardware procurement is a time-consuming process-- at least when measured in software development time scales. The availability of on-demand platforms like Amazon Web Services have mitigated the impact somewhat, but at Moz’s scale, it is much more cost efficient for us to run on our own hardware. From an operations perspective, the ideal scenario is to have a few large procurement batches with largely uniform hardware and long lead times. This often directly contradicts the developer requirements of frequent, widely disparate resource requests with very short lead times. Also, unlike a fresh entrant, we did not have the option of starting from scratch. Any solution would have to be able to handle both legacy workloads as well as new development efforts and be flexible enough to evolve with Moz’s needs.RogerOS

RogerOS is our take on how best to solve the problems outlined above. The name is a bit of a misnomer for it is not, in fact, an actual operating system. However, it does have some similarities. The best way of thinking about it is by the name we gave it during its development period. The development team referred to the project as the ClusterOS project. Just like a desktop OS abstracts the physical hardware and presents a uniform, higher level interface to the user, the ClusterOS does the same thing to a data center or a machine cluster. It abstracts away the cluster hardware and presents a different, higher level interface. This concept is not novel. Similar systems have existed for quite some time. Indeed RogerOS draws most of its inspiration from Google’s Borg system. The following sections outline the system in greater detail.Design Goals

The second post goes into the details of the design goals, but fortunately, it is easy to summarize the overall goal. We wanted to provide developers with a system that let them -- Go from code on their laptop to a prototype running in the data center in less than 5 minutes.

- Go from a running prototype to a staging version capable of taking limited external traffic in less than a day.

- Go from a staging environment to a full fledged, production system in less than a week.

- Be able to deploy new versions in less than 10 minutes.

- Not be limited in the kinds of workloads they could run on the system, so a system that could only do VM’s, or containers, or batch workloads was out.

- Focus on the application code as much as possible. The system should do as much of the heavy lifting of dealing with the practicalities of running the applications like load balancing, monitoring, logging, failure handling, scaling, etc.

Design

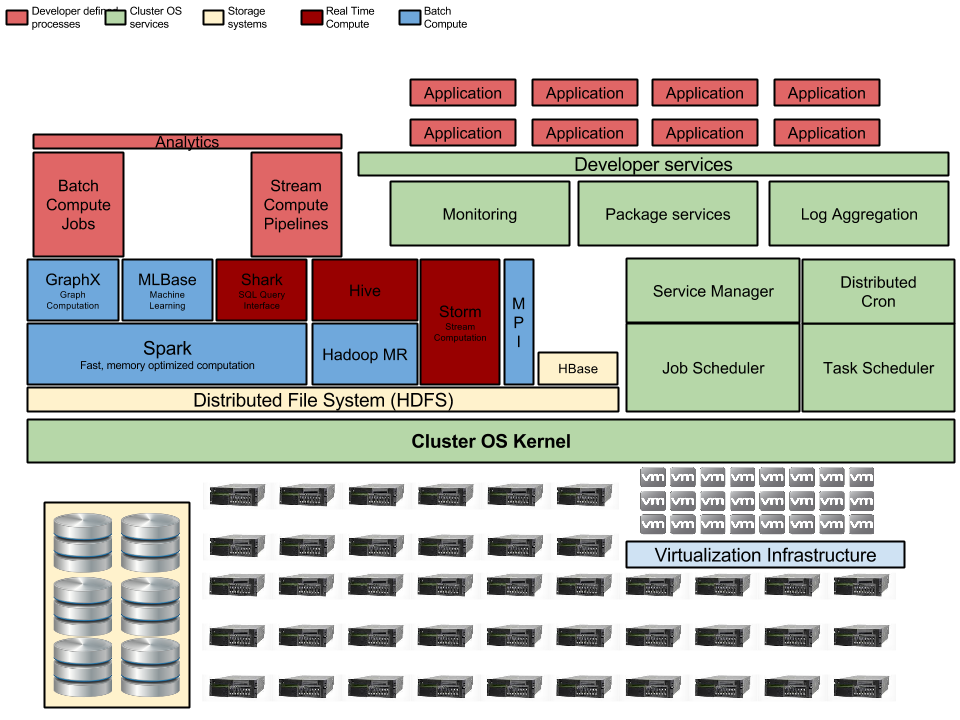

The core of RogerOS is Apache Mesos. Given the design goals and the flexibility that would be required from the system, Mesos was pretty much the only viable option. However, Mesos at its core provides a general purpose resource scheduler. Achieving the goals for the project required building an ecosystem around Mesos. Mesos corresponds to the ‘ClusterOS Kernel’ in the architecture diagram below. The diagram above shows the overall architecture. As mentioned, at its core, RogerOS has the Mesos scheduler, with a variety of synergistic services integrated tightly with the core. The second part of the series goes into the details of the design.

The diagram above shows the overall architecture. As mentioned, at its core, RogerOS has the Mesos scheduler, with a variety of synergistic services integrated tightly with the core. The second part of the series goes into the details of the design.