Browser Caching to Improve Site Speed: How to Check and Implement It

Site speed is what stands between your website and your potential visitors. Since the yellow pages are as archaic as the telegraph and the horse and buggy, potential customers’ first impression of your business is made by their initial visit to your website. If it is slow, they will often press the back button, redirect away from your site, and find a better faster-working site. Even if you run a blog or an individual webpage, fewer visitors will come to your page if they have to spend a lot of time opening it.

Additionally, slow speed can hamper your site’s ability to be found through search engine searches. It is well-known that websites owners spend a lot of time and money trying to get their websites on the first page of a Google search. In fact, one of the factors that Google takes into account before ranking websites is the site’s speed. Google accomplishes this through its ranking algorithm. Besides poor SEO, slow speed simply means less money. If your page isn’t among the first to come up in a search, your potential customers or visitors will be redirected elsewhere.

In short, the speed of your site is critical in furthering your business’ profitability or your website’s popularity.

First, let’s see how to check site speed. There are many ways but we’ll discuss a select few.

Site Speed in Google Analytics — If you set up Google Analytics on your site, you can find the speed report in Content->Site Speed->Overview. This gives an idea about the average page load time by browser, territory, and page.

In Content -> Site Speed -> Page Timings, you can see which page is the slowest or fastest. You can also analyze how your bounce rate depends on the page’s loading speed. It is also possible to compare the site speed for different browsers or operation systems. For more detailed information, see Site Speed in Google Analytics.

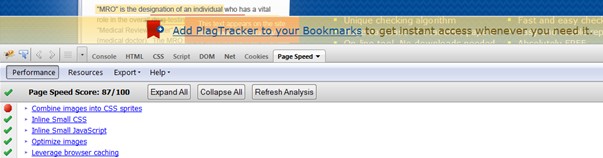

Another Google Tool is PageSpeed Insights, which runs a test to get your site speed score. The maximum is 100. Google, Facebook, and Twitter all have 97. We ran a test for our site Plagtracker.com and got an 88, which is good but still leaves room for improvement. This tool gives suggestions on what to change by dividing them into high, medium, low, experimental, and already done priorities. By clicking on each suggestion, you get more details on how to implement them as well as the link to Google’s Best Practices. In my opinion, this tool is very user-friendly, easy to understand, and helpful.

What I like the most is that you can install this as an add on to your browsers and then you can check the speed without not leaving the page. In Firefox, it’s in the Firebug add on. This is very well-known among experienced web developers who deal with HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. The results look like this:

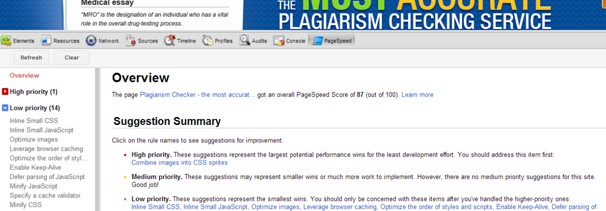

In Chrome, they look absolutely the same as in PageSpeed Insights:

Tools.Pingdom helps to review more technical issues.

Let’s take a look at what happens when a user enters a domain name in the address bar and clicks enter. First, the browser looks for the IP address of your site on the DNS server (Domain Name Service). Then it receives the IP address of the server where the site is hosted. The server looks for the site’s index file and sends it back to the browser. The same process is performed for each file that is used on the site, i.e. each CSS file, JavaScript file, images, sounds etc. The more files you have on the index page, the more time that’s needed to load the site.

Tools.Pingdom helps to see and understand how much time the browser takes to look up your DNS server, to perform an SSL handshake, to connect, to send data, to wait, and to receive data from your server. You just put in the URL and then receive data in such a format.

![]()

Each tab gives more detailed information with numbers, colors and graphs.

![]()

Webpagetest is also very similar to Tools.Pingdom. But it gives a wider range of locations to test and web browsers to choose from. There is also a compare feature that you can use to compare several pages and see how each page performs at once.

If you have a mobile version of your site, you may also check it here. But this tool works slower than previous ones described above and is full of ads that make the user experience less positive.

There are also some other tools to check the site speed with. Feel free to share which ones you have used and liked the most.

With these checked sites, we can see that browser caching is among the high-priority suggestions given by Google.

The internet works on the principal user server by using HTTP protocol with sites using headers to interact with the server. Browsers request the page from the server sending headers, http://pgl.yoyo.org/http/browser-headers.php, with all the same repeats and needed files for the correctly and fully displayed page. Each request server, therefore, sends a response with the specific browser instructions. Some of the headers are also responsible for client-side caching.

Once every session when you open any site, your browser checks whether or not your local file copies have expired and then it decides what to do next. This means whether it should load fresh copies or use existing ones.

With headers, you can set properties of your site’s cache behavior:

- No-cache – This prohibits caching. It is useful for updated pages, like news portals.

- Public – This enables caching on proxy servers.

- Private – This allows caching only for local usage.

- Max-age – This sets the expiration time in seconds.

- No-store – This means that your page contains some private data that can’t be stored.

Here are some examples of META tags that control cashes.

<META HTTP-EQUIV="CACHE-CONTROL" CONTENT="NO-CACHE">

NO-CACHE value can be replaced with any of the above-mentioned methods. It only depends on what you want to achieve.

To check whether or not your local copy has expired, use

<META HTTP-EQUIV="EXPIRES" CONTENT="Mon, 26 Nov 2012 11:12:01 GMT">

CONTENT="Mon, 22 Jul 2002 11:12:01 GMT" tells the browser that this file will expire on July 22, 2002 at 11:12:01.

Here is the full list of HTTP headers at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_HTTP_header_fields.

The easiest way to set up client-side cashing is to write some simple lines in .htaccess file. The following sets different cashing times for different types of files.

# 4 weeks

<filesMatch "\.( jpg|jpeg|gif|png)$">

Header set Cache-Control "max-age=2419200, public, must-revalidate"

</filesMatch>

# 1 day

<FilesMatch "\.(xml|txt)$">

Header set Cache-Control "max-age=86400, public, must-revalidate"

</FilesMatch>

*the code above allows you to keep jpg, jpeg, gif, png images cached for one month and xml, txt files for one day. You may add more file formats and change the max-age. Must-revalidate directive tells the browser to check file for freshness each time it’s being loaded, despite the max-age parameter.

Besides browser caching, you may also use server-side caching when files are saved on the server.

I would also recommend reading mnot.net and Google Best Practices Caching . These are great resources with technical details.

The main issue when using any kind of caching is to remember how often your site will renew its content. If you have a new, fast developing site with a lot of changes going on, better keep your max-age as minimum as possible. But if your site is not so much changed and you update it rarely, do not be afraid to extend the max-age. If you incorrectly configure caching, your clients may get stale content. Be sure to get all the aspects of cache-configuring techniques before starting.

On the other hand, site caching is a very powerful instrument to make you website faster and more user-friendly.

This YouMoz entry was submitted by one of our community members. The author’s views are entirely their own (excluding an unlikely case of hypnosis) and may not reflect the views of Moz.

Comments

Please keep your comments TAGFEE by following the community etiquette

Comments are closed. Got a burning question? Head to our Q&A section to start a new conversation.